English: A Communication Bridge or Language Destroyer?

- Jenna Thirtle

- Nov 11, 2021

- 4 min read

JENNA THIRTLE on the global influence of the world’s most dominant language

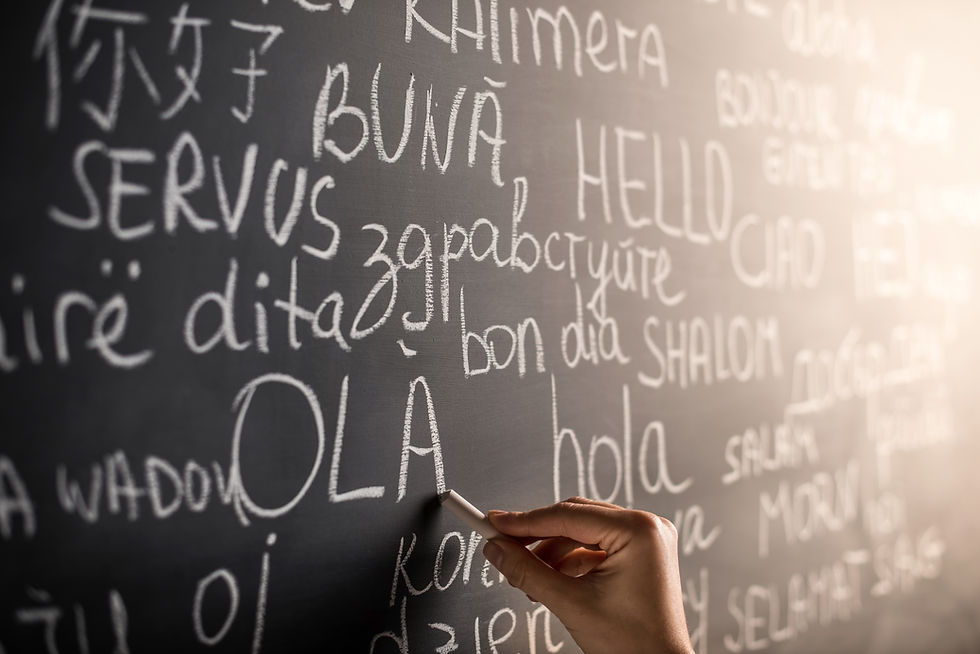

A German, a Frenchman and an Italian stood talking to each other on a street corner. No, this is not a joke. This is something I saw whilst in Slovakia. Now it may come as a surprise to find out that they were discussing bus times and even more of a surprise that I do not speak French, German or Italian, and my Slovakian is terrible. I know what they were saying because they were speaking English. Here is a prime example of English being used as a ‘lingua franca’. There was no native language in common between these people, so they chose to use English.

But why was English their lingua franca of choice?

How many people speak English and why?

We will all have a varying degree of knowledge about the British Empire. While the British Empire has mostly gone, except the Commonwealth, the linguistic imprint it left across the world lives on. An estimated 1.35 billion people (a fifth of the world’s population) currently speak English as a first or second language worldwide (Statista, 2021).

But the British Empire broke down a very long time ago, so what is keeping English alive?

One main reason is business. Many top employers around the world require a certain level of English proficiency. Universities around the globe also require prospective students to be able to use English 'without effort' (B1 level) to study many courses (British Council).

Another reason is opportunity. Many high paying jobs, such as in the STEM* sector, require employees to speak English. Whether you are reading the latest developments in your field of study or networking around the world, the chances are you will have to use English. Mooney and Evans (2019: 45) go as far as to claim that “people who wish to enter the international job market cannot compete for jobs if they do not have a suitable of fluency in the 'right' form of English” (e.g., UK English, American English or Australian English).

Even Polish journalists, for instance, need to be proficient in English. If they wanted to write about Marcin Bulka's journey at Chelsea but could not read the English reports about this beloved Polish player, how could they report about it back in Poland?

English and endangered languages

So clearly, the German, the Italian and the Frenchman knew what was good for them when they learnt English. But is it fair to ask equally great nations, tribes and cultures to learn this one language if they want to excel in a field or live an easier life?

Movements such as 'English Only’ in America, a highly multicultural country, campaigns to exclude non-English languages from educational, cultural and political life (see, for instance, this recent BBC article). These movements can and have been highly detrimental to the other languages spoken in the country and may contribute to further endangering already threatened minority languages until they eventually disappear. A language ‘dies’ because the last speaker or speakers pass away, and no one is left who speaks that language. The influence of English colonialism is indicated by the loss of indigenous (aboriginal) Australian languages. Of 250 languages before the 18th C English invasion and subsequent colonization, only 60 are now considered healthy (see here).

If you think this phenomenon only applies to small communities on the other side of the world, think again. Manx, the language of the Isle of Man, was declared ‘extinct’ in 2009 with its last native speaker Ned Maddrell, passing away in 1974. It is now, however being revitalized with up to 2,000 now learning to speak it as a second language (Guardian, 2015). Cornish, the language native to Cornwall, died out as a first language at the end of the 18th century but, like Manx is currently being revitalised (BBC, 2018).

Do these languages not deserve the same respect and treatment just because they were not chosen by a select few of government officials to be the 'official language' of a country?

The pressures to use English

It is true many people benefit from the income boost learning English has. In some countries, workers can earn up to three times more if they are fluent in English. But how many people from these countries can afford the cost of doing English courses to get these higher-paid jobs? The tempting rewards for many people outweighs the cost. Companies make tremendous profits from teaching English, creating resources and charging for qualifications. Higher wages and teaching courses boost the economies of native and non-native English-speaking countries. Clearly, the price of potentially losing a native language is not too high for these countries. We are losing parts of our world's history, for what? Convenience sake? Higher wages?

Perhaps however, I am slightly ill-equipped to have strong views on this? After all, it is not me or you who is having to choose between getting a higher paying job and speaking a minority mother tongue language.

As native English speakers, we will struggle to understand these dilemmas until a time comes when perhaps another language starts to replace ours.

*STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics

Written by Jenna Thirtle

_ed.png)

Kommentare